When actor Bryan Cranston took the Bing Theatre stage Jan. 21, a week after his Oscar nomination for Actor in a Leading Role in Trumbo, he made a believable case that the awards race has not been occupying his thoughts.

Thinking of other actors as competitors is damaging, he told the full house of USC School of Dramatic Arts students there for another in the series of Spotlight@SDA events interim dean David Bridel has arranged and moderated this academic year. Said Cranston: “I’ve been at this 37 years and I’ve seen the chip of resentment grow into a chasm. It will destroy you.”

The chief importance of awards, said the recipient of three Emmys, one Tony, four SAG awards, one Golden Globe and several others, is that they open doors for other projects in which to act, write, produce or direct.

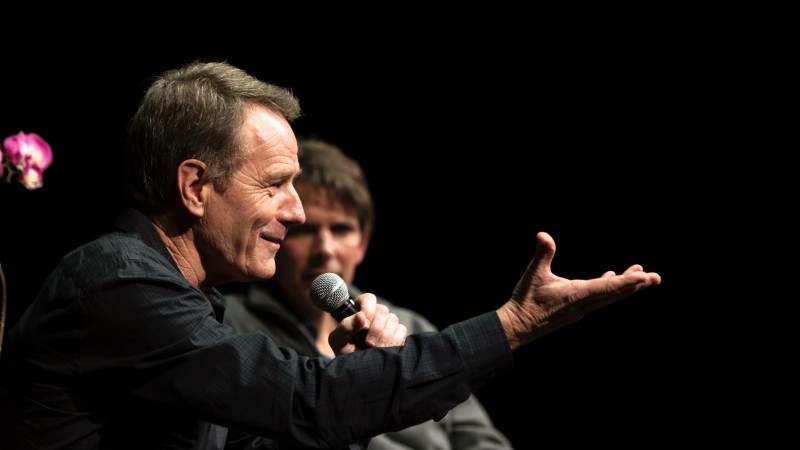

Bryan Cranston. Photo by Michael Rueter/Capture Imaging

Cranston was thoughtful, charming and very, very funny, bringing the house down several times during his hour on stage as he recounted anecdotes from his early career.

His first acting job was in a deodorant soap commercial. He played a skunk, in a full costume with tail. “So that’s what’s in store for you,” he told the students with a grin. “It’s a long, long path.”

He observed that all of the Dramatic Arts students in the audience “have far more education in acting than I do.” Cranston has firsthand experience with what USC acting students learn, as his daughter, Taylor, is a 2015 graduate of Dramatic Arts. (He proudly relayed the news that she has the lead in a MTV series that starts in April.)

As a teen, coming from a broken home and looking for a father figure, Cranston decided his future would be as a policeman. He studied police science at Los Angeles Valley College, and did well in it, immersing himself in the major so completely that he neglected to take any electives. Needing one, he took an acting class. “And at 19 years old, all of a sudden, my life changed.”

In the first day of his first class, he had a scene where he was to make out with a young woman classmate on a park bench. Cranston gave the USC audience a hilarious rendition of how the scene went, with the make-out session growing more and more heated and Cranston believing the young woman was really into him. After class, he asked her out, but was rebuffed. It suddenly struck him that she had been acting. “Now, I’m dizzy,” he recalled. “It knocked me out. A minute ago, I was a police science major.” But after that experience, he switched to acting.

Cranston said he stumbled upon an important way of looking at his career more than two decades ago, and it changed his life and the way he looks at success. “I thought when I was going on an audition, I was trying to get a job,” he said. But he realized he was giving up all his power to the casting directors and producers. He changed his thinking. “My being there was to give something to them. It’s like giving a present. You feel good. It’s given with love.

“My job is to create a compelling, interesting character. I’m thinking ‘how can I help (the people in the room) solve their problem?’ It is not to get something from them. If they feel need, you’re dead.”

That change in philosophy was enormous for him. “Once I adopted that point of view, my career took off,” he said.

Cranston credits his blue-collar upbringing with his lack of desire to chase fame and riches. From his humble start playing background characters, he has taken acting classes, carefully researched his characters and looked for roles where the scripts were well written.

“The hardest work you’ll ever have to do is on poorly written material,” he opined.

The actor deliberately keeps himself in the dark about how much money he is offered so he can choose projects for other reasons.

What “civilians” – people outside the industry – don’t understand is how hard people in the entertainment business work, he said. “You are gonna work your asses off.” The business is “relentlessly difficult.”

“A career in the arts will only happen if there’s a generous sprinkling of luck,” he said. “But sometimes it’s luck when it doesn’t happen.” An example he gave was of testing for comedies at both Fox and NBC. He didn’t book either of them, but then got the part of the sweet, goofy dad in Malcolm in the Middle. It turned out that the other two pilots he had wanted to land did not sell.

Interim Dean David Bridel and Bryan Cranston. Photo by Michael Rueter/Capture Imaging

After Malcolm, he received more offers to play sweet, goofy dads.

But he went the other way, creating the now-iconic character of Walter White in Breaking Bad. “The script moved me greatly. I thought about it, dreamed about it.” He knew the character so well that when he met with series creator Vince Gilligan “I was telling him what Walter White looked like.”

A student asked him how he was able to let go of Walter White at the end of each filming day and not have the character’s darkness affect him.

Cranston said that after shooting, steamy hot towels would be wrapped around his face and head in the makeup room. “It lifted that energy out that I didn’t want to take with me.”

So perhaps it wasn’t so confounding that the first acting he did after Breaking Bad was the film Godzilla. “There’s real value in pure entertainment,” he said. “There’s value in an actor having fun.”

He advised students to save their personal dramas for the stage and screen. “Create an environment in your personal life that is sound, and then you can go crazy in your creative life.”

When choosing roles, actors should “dare to be embarrassed” and take jobs that scare them. “It would scare me doing a musical on Broadway because I’m not a singer,” he admitted. “So I should do that.”