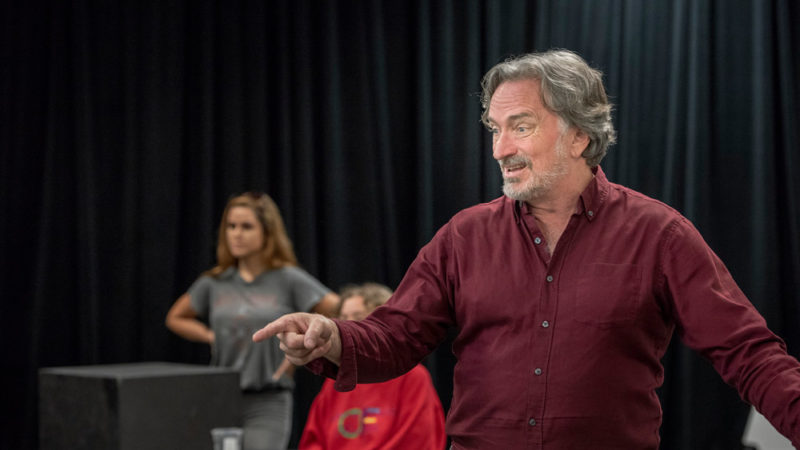

In light of recent circumstances, the USC School of Dramatic Arts has asked our faculty to share honestly with our community, about difficult discoveries, small victories, silver linings, and more. As we learn and grow as a community, staying connected is very important to us, and we hope you will find these dispatches comforting in uncertain times. Our next letter comes from Brent Blair, Professor of Theatre Practice in Voice and Movement and Head of Theatre and Social Change.

On April 27, students from the USC School of Dramatic Arts and USC Price School of Public Policy joined with formerly incarcerated lifers to produce a play called Pause, as the fulfillment of the two schools’ collaborative class, Performing Policy: The Justice Project. This production, of course, was not a live theatre, but on Zoom. The auspicious collaboration between a local non-profit restorative justice organization and two USC schools is in its second collaborative year, this time with support from the provost’s Arts in Action grant administered through Visions and Voices. The prospect of interactive Forum Theatre in the tradition of Theatre of the Oppressed, supplemented and supported by rigorous research from policy students, was a dream that began during a 2018 lunch between myself and David Sloane from Price. The first performance was held in the Scene Dock Theatre last year to a capacity audience, filled with friends and family of USC students and community partners whose lives were touched by violence, both perpetrators and victims.

This year, the project was extended and ambitiously designed to produce an original play about the challenges of supporting, implementing, and sustaining restorative justice programs in prison. These programs would potentially offer serious offenders a radical option to healing and hopeful release by placing them in healing circles among themselves, and then between themselves and their victims. The evidence supports the notion that when prisoners participate in such alternative programs, there is a reduction in recidivism, a decrease in episodes of violence inside and outside of prison, and a measurable psychological relief for victims of violence. Once again, some 17 SDA and 26 Price students met twice weekly with Tobias Tubbs and Christian Branscombe, both former lifers whose dedication and restorative justice work led to their paroles and commutations within the last few years. We had been preparing for the main event, an interactive session in the Scene Dock Theatre on April 27.

Then, by late March, we scrambled to find an alternative to a live performance as all the world went online and Zoom became our new classroom.

We struggled at the first. Our partners were new to the technological age, having been in prison for the better part of the last three decades and having never used the internet, much less Zoom or Skype. Students traveled back home to live with friends, family, grandparents, some on farms without WiFi, and we needed to battle the sometimes popping, crackling, unresponsive internet that slowed our delicate conversations and made us struggle to be sure we understood each other.

In early April, thanks to many breakout weekend Zoom sessions with willing students and our community partners, we settled on a towering proposal – to deliver a one-hour devised theatre piece with interruptions called “policy pauses” in the form of stunning PowerPoints with voice overs, some emotional interruptions to teach the unsuspecting or unwitting viewer/Zoom attendee about the exigencies of day to day prison life, from deep mental health issues to the very real, very pressing dangers of COVID-19 while in lock-up. We called these entre-acts “interstitials” – and we were now able to imagine the use of video, audio, and deeply personal voice acting.

Going on Zoom forced us to realize how the camera can be like the prison cell, and our students had the shocking and unexpected takeaway of feeling somewhat trapped while reconstructing the story of two men who found healing through art-making in prison. We were, in a parallel way, finding our own healing as a cohort of Theatre and Policy students, spread all over the country with all kinds of challenging circumstances, through the production of art while in quarantine.

The final event was not without last minute challenges – our script was too long, we had massive sessions on Sunday prior to Monday cutting lines, stage directions (How shall we approach this? Read them? Show them on the screen? We opted to create artistic PowerPoints during some of the actors’ scenes and cut unnecessary descriptive stage directions). We had to take crash courses in Zoom Webinar, which differs from the classic Zoom we have been using for our classes. We had an issue with our lead actor getting bumped off and not being able to get back on after we started the show – we discovered this only after we started and he missed his cue! But it was easily remedied, the Zoom attendees from all over the world (Australia! Ukraine!) were accommodating and generous, and the event was superbly received.

I am sure I learned more doing this project than I taught, but principally it was a leap of faith to trust technology when the comfort zone is live interactive theatre. By being forced to deliver this play on Zoom, we actually reached double the audience from far wider places (outside of the U.S.) than we might have otherwise. Perhaps most fortuitously, we found we had some surprise guests. You see, both Chris and Tobias had been commenting throughout the semester that a major influence on their lives was the author and psychologist James Gilligan, whose book on Violence frames the issue in terms of shame and guilt, both central themes to our play. When the electronic curtain “rose” at 8:00 p.m. that night, I realized James Gilligan was among the participants and quickly “promoted” him to a panelist. He joined after the show on camera and was clearly moved, as were our community partners, by the show.

The event was by all accounts a success, but the work doesn’t stop here. We had intended to develop the play over the summer, hire some local actors and present a reduced version of it at a community gathering for U.S. Representative Karen Bass in August. As times have changed dramatically, we have re-conceived this idea to imagine a transcription of our interventions during the event, develop a new short play that shows the challenges and difficulties of implementing restorative justice, hire a whiteboard illustrator to display the dramatic obstacles presented by district attorneys, politicians, some victims of violent crime opposed to restorative justice, and the prison workers’ union. All these “antagonists” to restorative justice were prominent figures in our play, and all represented challenging arguments against reform. We envision hosting another Zoom Webinar and hope that the Congresswoman will be able to attend with Zoom attendees around California whose lives are touched by the prison system or violence. With the actors and the whiteboard illustrator, we hope the message of impossibility will be clear, and that the Zoom Webinar can become a people’s forum for imagining new legislation that would offer real hope moving forward. In Theatre of the Oppressed terminology, this act is called Legislative Theatre, only in our case, it may be Legislative Zoom-theatre.

Pause was a tremendous success, not in spite of, but perhaps precisely because of our COVID-19 quarantine environment. It left all of us wondering how, even after we return to “normal” (is there such a thing?), we might continue to incorporate an online component to our interactive community-based theatre for social change work.