For more than 20 years at regional theatres across the country, designer Sibyl Wickersheimer has been using her scenic designs to help give theatregoers a window into the playwright and director’s artistic vision. The metaphor she employs to describe her function — both as artist and instructor — is positively, well, nutty.

“I always try to crack the play open for an audience in a way that allows the ideas in the design to bring the ideas of the play to light on stage,” said Wickersheimer, an assistant professor of scenic design at SDA since 2010. “It’s been an ongoing discovery: How can I do the same thing for my students in terms of cracking open the nut that is set design and how can I show them they can have an impact on a performance that ultimately then has an impact on an audience?”

With increasing frequency, Wickersheimer has employed the students from her theatrical design classes as fellow nutcrackers. When she takes on a professional assignment either locally or out of state, Wickersheimer brings parts of that experience into the classroom. Or, when feasible, she brings the students to the venue itself.

She has brought her students to a pair of recent productions both of which are concluding their runs in October. The run of Robert O’Hara’s dark comedy Barbecue at the Geffen Playhouse lined up such that Wickersheimer arranged for her students to visit the theatre, observe an invited dress rehearsal and purchase discounted tickets. For her production of Laura Eason’s Sex with Strangers earlier in the year — also at the Geffen Playhouse — Wickersheimer arranged for students from her Methods and Materials and Advanced Set Design classes to watch the technical rehearsal (AKA “tech”) and get a backstage tour.

Barbecue at the Geffen Playhouse, designed by Wickersheimer.

While there was no pilgrimage to Ashland Oregon for the Wickersheimer-designed staging of Shakespeare’s Richard II for Oregon Shakespeare Festival (closing Oct. 30), Wickersheimer developed a research lecture designed to help illustrate some of the challenges of her design process. Wickersheimer, who had not designed a Shakespeare play in more than a decade, initially found the assignment intimidating. But by bringing her work into the classroom, she used the experience — and her feelings about it — as an educational tool.

“I have to say that my fear turned into a really great story and example for my students,” she said. “I let them into a window that I had been describing to them, but really, until I put them through my process, I don’t think they fully understood what I mean by research. It incorporates so many different elements of historical research and understanding the text, but also ‘how do I help the process in making the production meaningful?’ ”

Wickersheimer talked about Google mapping the location of all the castles that appear in Richard II to demonstrate how their proximity to each other influences some of the action of the play. Later, she gave her students the chance to wrestle, as she had done, with a specific design challenge.

Just before conceding his kingdom to Henry Bullingbrook (the future King Henry IV), King Richard arrives on stage wearing an enormous cape that drapes over a large section of the stage. When he relinquishes the throne, the cape falls and, in a subsequent scene, it is eventually swept up into trash bags.

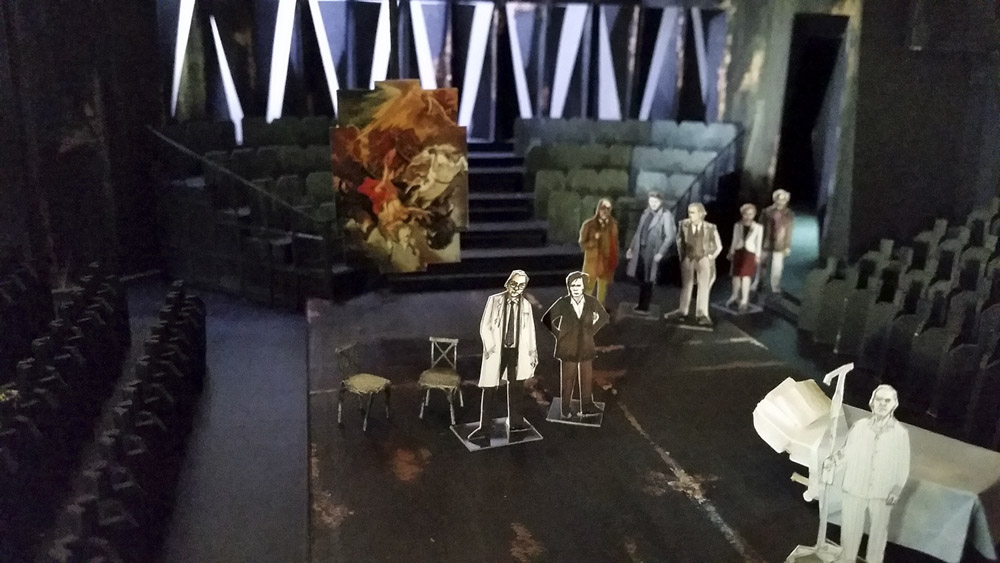

Concept for Richard II set.

“It was a great metaphor. It was a very tricky piece to design,” Wickersheimer said of the cape. “I brought it to my Methods and Materials class in the spring and I said to them, ‘Here’s my challenge as the designer. Here’s the moment and here’s the idea we’re trying to create on stage.’ ”

The hands-on exercise involved used pleating to address the challenge. The students used folding paper to come up with techniques for covering a large area. When they ultimately were shown pictures of the actual cape, Wickersheimer heard plenty of giggles and gasps.

“It’s definitely a great example of how I bring set design work into the classroom in a very tactile way,” she said. “Set design encompasses so many skills and so many different areas of communication, inspiration and evaluation that it’s very hard to explain how you might end up at something and what makes meaningful design. So bringing them into my process, I make discoveries I find is also essential to my understanding.”

For Barbecue, Wickersheimer dealt with a consistently humorous script set largely in a non-descript park somewhere in middle America. Although O’Hara’s script is funny, nothing about the set was supposed to draw attention to the play’s humor, said Wickersheimer who largely tried to “stay out of the text’s way.”

Building of the set for Barbecue.

A native of Champaign-Urbana, Ill., Wickersheimer based her design on a park she found near her hometown. Adding vegetation, she added is always an additional challenge.

“From the get-go, I felt it had to be naturalistic which is always a trial for me because I think in a much more abstract and conceptual way,” she said.

By the time he graduates, senior Liam Sterbinsky, will have taken four classes with Wickersheimer. This semester, the professor is mentoring Sterbinsky’s design of George F. Walker’s Escape from Happiness, performing Oct. 20-23 in Scene Dock Theatre. The play is set in a kitchen, and Sterbinsky — whose concentration is lighting design — is trying to negotiate the use of multiple irregularly shaped cabinets.

According to Sterbinsky, Wickersheimer’s laid back temperament has served him well.

“She’s very calm and patient with her students,” Sterbinsky said. “I’ve had some challenges with this show and I’ve had plenty of conflicts just with doing work outside of school. There has been a lot fighting for my time. She has been understanding of that and has helped me prioritize and figure out what to attack next.”

“Maybe with a different mentor, I could see someone else getting more frustrated,” Sterbinsky continued. “That wouldn’t necessarily help the situation. It would make it worse. Sibyl is really great in that way.”

Wickersheimer comes from a teaching family. Her father David taught in the School of Architecture at the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana for 30 years.

“I don’t know that I was a good teacher until I had several years under my belt,” Sibyl Wickersheimer said. “I think that requires many different things being really patient and taking things slowly so you can actually show students how to do something, how to develop a skill or many skills and how to express themselves with that skill. They still surprise me on a daily basis, and that’s a wonderful place to be.”