It happens every year: On the first morning, they’re somewhat wary strangers. They arrive from all points of the globe, jet-lagged, with myriad questions, expectations, doubts, hopes. But just four weeks later, when it’s time to leave, the students of Creating Characters find that they have expanded their imaginations and experiences, formed an ensemble, and — amazingly enough — created and performed their own play.

Creating Characters, along with the Acting Intensive, is part of SDA’s Summer Theatre Conservatory, a four-week program for high school students in which they earn college credit, study with professors from the School of Dramatic Arts, and get a sense of what it’s like to be an undergraduate at USC. This summer, students from as far away as China lived in the dorms, attended class sessions from 9 to 5, Monday through Friday, and discovered a bit of what it’s like to be independent — responsible for doing their work and managing their time without the prompting of parents — and, even more important, what it’s like to be an artist.

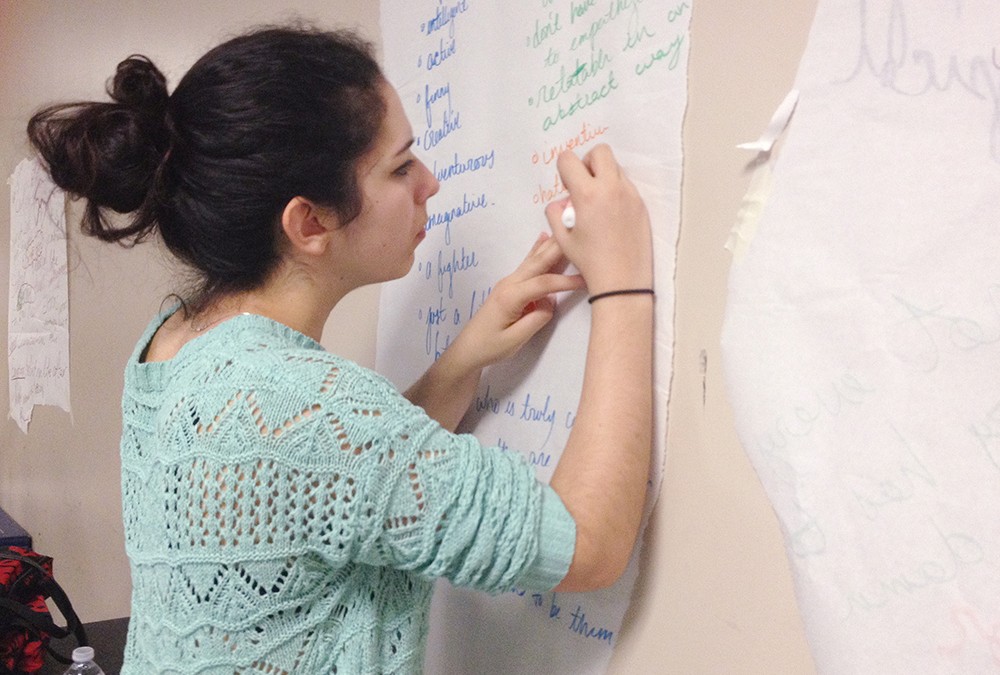

Emphasis, of course, is on Process. Collaboration. Empathy. Metaphor. Creating Characters is a hybrid — not quite a writing class, not quite an acting class, not quite a production class. It’s an introduction to theatre making — and is very hands-on. A typical day might include writing exercises, improvs, developing a sense of character through movement and gestures, a play reading, some Viewpoints work, a brainstorming session, an exercise in collaboration. It’s all geared toward opening up students to imaginative impulses they didn’t even know they had, and demonstrating how to build something that is uniquely theatrical — together, as a team.

My co-teachers this summer, Madhuri Shekar and Jonathan Muñoz-Proulx, were quick to identify a few perennial obstacles the kids have to climb over before they can join together and make a play from scratch. First and foremost: It’s hard to collaborate — everyone is passionate, has their own ideas, and the give and take is really difficult, especially when everyone wants to make something that has meaning. Next, our students see far more films than they do theatre — so guiding them away from creating something that isn’t dependent on photographic reality is an ongoing challenge. And, as Jonathan noted, the closer we get to the final presentation, they all become “product-oriented and think only about tech.” Trying to get them to simplify and to start to envision a piece that is theatrical is part of the process. “I tell them, they can have trees onstage if they are the trees,” he said. “They can have sounds onstage if they make the sounds.”

My co-teachers this summer, Madhuri Shekar and Jonathan Muñoz-Proulx, were quick to identify a few perennial obstacles the kids have to climb over before they can join together and make a play from scratch. First and foremost: It’s hard to collaborate — everyone is passionate, has their own ideas, and the give and take is really difficult, especially when everyone wants to make something that has meaning. Next, our students see far more films than they do theatre — so guiding them away from creating something that isn’t dependent on photographic reality is an ongoing challenge. And, as Jonathan noted, the closer we get to the final presentation, they all become “product-oriented and think only about tech.” Trying to get them to simplify and to start to envision a piece that is theatrical is part of the process. “I tell them, they can have trees onstage if they are the trees,” he said. “They can have sounds onstage if they make the sounds.”

To emphasize the work-in-progress nature of the play the students create, we don’t use traditional sound and lights for the final presentation, just “vernacular technology” — that is, whatever we can generate from cell phones, flashlights, and the stray overhead projector that we scrounged the hallway of the McClintock Building. This helps, too, to get everyone’s mind away from film and into the realm of stage magic.

It’s a mad scramble as the presentation day draws near — and even after doing this for 12 years, I confess I still always worry if the whole thing is going to come together. But there is something about the will to create that drives everyone on.

In the end, the students performed a piece set at a residential mental health facility where various characters were haunted by their dreams. The text portion of the play was bookended by movement sequences, and within the overall story, each student got a spotlight moment for their character. As Madhuri noted, “The show looked amazing” — and that was without a fog machine, colored lights, and a dozen costume changes, which they were sure they couldn’t live without.

In the end, the students performed a piece set at a residential mental health facility where various characters were haunted by their dreams. The text portion of the play was bookended by movement sequences, and within the overall story, each student got a spotlight moment for their character. As Madhuri noted, “The show looked amazing” — and that was without a fog machine, colored lights, and a dozen costume changes, which they were sure they couldn’t live without.

“Wow. I didn’t know I could do this,” a 16-year-old from Beijing said after performing the brand new, collaboratively-written piece. The others nodded and looked at him, and a 15-year-old girl from Houston said, “But we did.”

About the Author

Paula Cizmar is an Assistant Professor of Theatre Practice at the USC School of Dramatic Arts. She is an award-winning playwright whose work combines poetry and politics and is concerned with the way stories get told in a culture — and with who gets left out of the discussion. Her plays, which include January, The Death of a Miner, Still Life with Parrot & Monkey, river: post-futurist, Candy & Shelley Go to the Desert, and Street Stories, have been produced all over the country, in theatres big and small, including Portland Stage, San Diego Rep, The Women’s Project, (NYC), Cherry Lane (NYC), Jungle Theatre (Minneapolis), and Playwrights Arena @LATC.