Jameelah Nuriddin

Jameelah Nuriddin BFA ’06 has made a career out of socially-conscious storytelling. Part of her success is an ability to adapt to new technology — and to pivot when obstacles arise.

A case in point: In 2020, Nuriddin was all set to direct a series of live-action short films urging young Black women in Alabama to learn about government and register to vote. She and her producing partner had grant money, had cast several Alabama teens and were ready to shoot.

Then, COVID-19 shut down production. Nuriddin and her crew switched to animation, using voiceovers from the teens. Although Nuriddin, an award-winning film editor, had not worked in animation before, she came to appreciate its creative possibilities.

“It changed me as an artist,” she says. “I had to adjust, but I found so much creativity while playing with a new medium to bring in many new ideas. It deepened my ability to tell a story because I couldn’t rely on some of the things I had always relied on.”

The animated docuseries, Shaping Our State, has been warmly received, and is being submitted to festivals. Nuriddin now is in talks to do similar work in Georgia.

“We want everyone to see the series because it has a very empowering message,” she says. “There are so many more states that need this and need to push more women of color to have positions of leadership.”

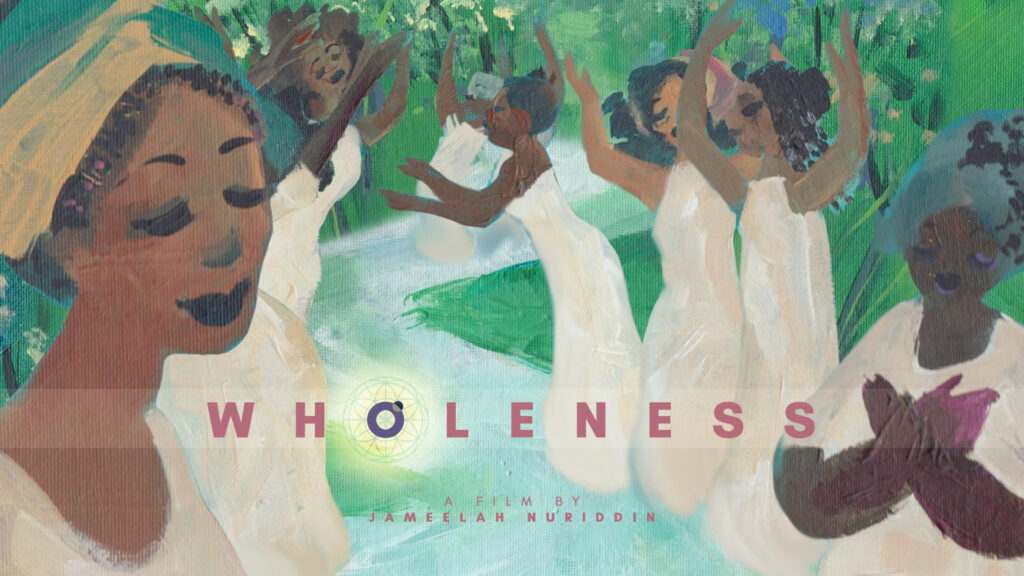

Nuriddin’s latest project, a short film about a Black woman’s mental health journey called Wholeness, just finished filming. It encompasses live action and rotoscope, which she describes as “a blur between live action and animation, where you paint over live film.” It is a deeply personal project where she employed many of her talents — as an actress, director, writer, editor and producer.

She hadn’t planned on taking on all those roles herself, but she decided not to wait until she could afford to hire others. “I wanted to have more people have credits on the film, but I didn’t want to wait,” she says. “I felt really resolute, like this is going to happen. And I think a lot of artists can recognize that in themselves.”

Nuriddin’s storytelling almost always focuses on giving voice to marginalized communities, particularly Black women. Another recent project has been video interviews with scientists, funded by the National Institutes of Health, to demystify scientific fields of study for young people of color. The videos release in 2022.

An artist who does it all, Nuriddin starred in, directed, wrote, edited and produced the short film Wholeness.

The Atlanta native, who now lives in Los Angeles, is generous in her praise for her School of Dramatic Arts professors. Many taught her lessons that she uses daily.

“Brent Blair is one,” she says. “He taught a lot of Linklater (voice work), and that has stayed with me my entire life. I still do the exercises any time I’m getting ready to perform or do an audition. And I learned tempo from Stephanie Shroyer, who is a very beautiful physical theatre teacher.

“Physical theatre connects to editing because when you are editing people, you are editing

their bodies and their facial expressions. When people blink or exhale to get a breath, that’s the time to cut to something else. It’s a natural rhythm, and if you betray that, there’s something off about it.”

Nuriddin, who first learned editing in high school using VHS tapes, jumpstarted her abilities when she came to USC. “It was through the theatre and film friends I made and the short films we would make and the 48-hour film festivals that they had on campus that I started to edit all the time,” she says.

Admittedly, Nuriddin has been quick on her feet to learn new things. “Even though the settings change and the details change, the core of storytelling remains the same. People are looking for an emotional connection, and a protagonist who has to overcome something, internal or external. The more you, as an editor, work to accentuate what the actor, director and the writers already have put into a film, the better the product is. And that’s why a lot of people call the editor the final writer of any project.”

She credits the rise of digital cameras and the revolution in streaming and distribution for a welcome expansion in the universe of people able to tell their stories. “When film was very expensive, you needed a gatekeeper with tons of money and you had to convince a boardroom full of people to do something,” she observes. “Now, you can literally get a few of your friends together, and if you do it well enough, it can become a wild success.”

This article appeared in the 2021-22 issue of Callboard magazine. Read more stories from the issue online.