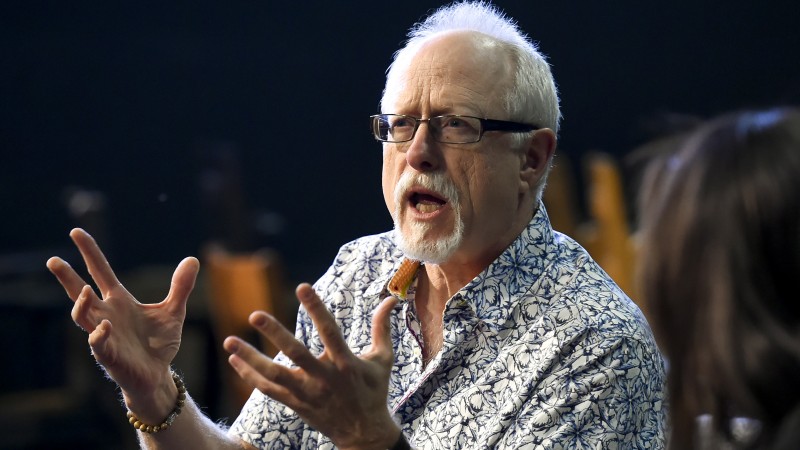

Robert Schenkkan, the Pulitzer Prize winning playwright, was warmly welcoming to student writers who want to follow his path. In a talk with USC School of Dramatic Arts students Oct. 28, he acknowledged the lack of financial rewards – even for frequently produced playwrights – but expressed deep affection for his profession.

“I love this art form,” he told the students who filled the Massman Theatre. “There’s a reason it has endured. The gathering of strangers in a room to share the telling of a story is so potent. It speaks to us in a profound way.”

Schenkkan is the author of many well-received plays, including Pulitzer winner The Kentucky Cycle, a nine-play epic that follows families in eastern Kentucky from 1775 to 1975, and All the Way, last year’s Tony Award Best Play about LBJ, political power and morality during the pivotal year of 1964.

Schenkkan was on campus as part of a Visions and Voices Signature Event co-sponsored by USC Dramatic Arts. In the afternoon, he spoke to students in conversation with professor Velina Hasu Houston, director of the school’s Dramatic Writing Program. In the evening, he spoke to the general public at Town & Gown. At both events, he was relentlessly encouraging to students interested in playwriting. “Welcome aboard! So glad to have you here!” he told a senior in high school and a middle school student, both fledgling playwrights, who attended the evening session with their teacher and posed questions afterwards.

In the afternoon, the playwright was generous with advice to the undergraduate and graduate students. The following shortened responses represent a sampling of his carefully considered answers to their many questions.

What do you draw on for research?

When a project is fact-based, immerse yourself in that world. You want the smell and taste of it to be right. Characters, events and conflicts turn up in the research. For The Kentucky Cycle, most of my research was done in the library, looking at newspapers and letters. But it’s very easy to get lost in research. You can use it as an excuse not to write.

How do you decide what to include?

You can hardly accuse me of limiting myself in The Kentucky Cycle – it’s six hours. I go for an interesting conflict that is revealing of character that links toward the overall broad stroke of what I’m trying to say and answers the question ‘Why are we here talking about this?’ Ideally, I am looking for a moment that’s rich, chewy and revealing – a moment that does all that.

What are the special problems when writing about a real person?

It’s a challenging issue when you deal with people who actually existed. The closer we are to contemporary time, the more charged that gets. But I’m not a historian, and not a documentarian. I’m a playwright. I have a point of view. That’s why you buy a ticket.

You can’t have someone say or do something that they wouldn’t say or do. But it’s tricky, dealing with heirs. The Johnson family’s first response to All the Way was that LBJ never used the f-word. It wasn’t about Vietnam, his infidelities and Machiavellian tendencies.

How do you write about an antagonist who is a complete villain?

With villains, you’ve got to love them or at least understand them. I’ll sometimes create a fairly detailed imagining of the person’s childhood, when they are at their most vulnerable. What kinds of beauty do they respond to? What do they love? Approach them in the most compassionate way possible. Everybody is the hero in their own story.

When writing about social and political issues, how do you not go on a rant?

Nobody likes to be lectured. You need to bank your fire and focus on the story you’re trying to tell.

How do you organize inspiration?

Sometimes plays are inspired by an image; a daydream reverie. I’ll write to understand the image. In All the Way, I had to outline. I was dealing with so many characters and events.

Does your background as an actor influence you as a writer?

A lot. I never studied writing. I was a professional actor for 10 years. I tend to think in actor’s terms: action, objective, motivation. I think all the writers in this room ought to take an acting class.

What is your writing schedule?

I’m very disciplined about it. I get up early, go to the gym. From 8 or 8:30 until noon, I write, I have lunch and a 20-minute nap. I do it five days a week.

When I’m writing a draft of a new play, five pages a day is my goal. When you make a promise to yourself to write tomorrow, keep the commitment to write. And I don’t judge it until I finish it. We are our own worse critics: so merciless, so unforgiving.

The point is to finish it. Then you can say: I did this. Finish it, finish it, don’t stop yourself. That’s the worst thing.

One tip for successful writing.

If I’m writing well, and it’s time to quit, I’ll stop in the middle so I know exactly where I am. It gives me this great start the next day.

A second tip for successful writing (given at the evening program).

If I get stuck, I think about the problem right before going to sleep. Sometimes I’ll wake up in the middle of the night with an inspiration, but nine times out of 10, a solution emerges when I start writing the next morning.

Current thoughts on theatre.

I worry about theatre. It’s overpriced. It needs more people of color, more women. This week, the Dramatists Guild published “The Count,” which shows who gets produced in America. It’s pretty shocking. Only 22 percent of plays are written by women and women make up more than 50 percent of the audience. Only 7 or 8 percent are writers of color. It’s appalling. And the figures are true no matter if the artistic director or literary manager is male or female.

If we have more diversity in writers, our audience will diversify as well.

Advice for USC students.

There’s no reason you need to wait for someone to tap you on the shoulder with a magic finger. Right now, you have a lot of resources. You can produce your own work as often as you can wherever you can. By the time Bill Rauch, the artistic director of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, had graduated from Harvard, he had produced 27 plays all over campus. In dormitories. In dining halls. Everywhere.

Be your own instigator and don’t sit by the phone waiting. That’s such a drag.